An Introduction to Australian Politics and Government providing access to the Australian Commonwealth Constitution Act, Quick and Garran’s Commentaries on the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia (from the University of Sydney library), and my own notes on Nick Economou‘s lectures on Australian Politics.

AustralianCommonwealthConstitutionAct

Quick and Garran – Annotated Australian Constitution – fed0014

Sir Gerard Brennan’s Lecture A Pathway To A Republic, on constitutional change, including recognition of Australia’s Indigenous people: Gerard Brennan’s Lecture

I have also created posts on my own idea of social justice, and the insidious application of the concept of terra nullius in the Australian context.

The following are my comprehensive notes based on the 2010 Monash University lectures of Dr. Nick Economou on Australian government and politics. Since I created these notes there have been major changes with the prevailing governments in Canberra, but the history of our political system and the processes of government remain largely unchanged. This is a very useful primer for the political science student, not only in the Australian political system and its history, but in the machinations of Australian systems of government:

4.1 The Constitution

4.2 Revolutions

4.3 Liberalism

5.1 Federations and Federalism

5.4 The Constitution – defined

5.8 Liberal democracy – defined

5.9 Parliamentary Bicameralism

5.10 Separation of powers

5.11 The Crown

5.12 What the Constitution does

5.13 Why federate?

6.2 State and national constitutions

6.5 Conventions

6.6 S.96 – Financial assistance for the states

6.10 S.53 – The Senate and tax bills

6.11 S.57 – The double dissolution and joint sitting provision

6.12 S. 5 – The role of the Governor-General – Reserve Powers

6.13 What the Australian Constitution does NOT provide for

6.14 No Parliamentary Sovereignty in Australia

7 The Westminster System p.II

7.4 Ministerial Responsibility

7.6 Cabinet

7.7 Cabinet secrecy

7.8 FOI

7.10 Westminster Cabinet

7.11 Westminster – the Australian approach

7.12 The Australian Model

8.1 The 1975 Constitutional Crisis – 11 November 1975

8.2 How Parliamentary legislation is made

8.3 S.57 Australian convention

8.4 Political background to the crisis

8.5 Controversies in Australian Westminster practice

8.6 The 1975 Constitutional Crisis – Political background

8.7 72 and 74 elections – Senate obstructionism

8.8 Overuse of S.96 to force State compliance

8.9 S.15 – Replacement for casual Senate vacancy

9.1 1975 Summary

9.2 Constitution versus convention

9.3 Kerr prorogues the Parliament

9.4 Kerr’s argument

9.5 1977 – Change of Constitution

9.6 Use of S.96 to circumvent S.51

9.7 Problems of the Whitlam Government

9.8 High Court of Australia and pre-emptive constitutional advice

9.10 Changes since ‘75

10.1 The importance of the Public Service

11.1 As an example of Westminster Public Service

11.2 The difference between the public service and the public sector

11.5 Permanent departmental heads

11.6 The American model

11.7 Separation of powers

11.8 Hawke’s model – 1987

11.9 SES – Senior Executive Service

11.10 ‘Children Overboard’ & AWB affairs

11.11 Ministerial Advisers

11.12 The conventions of Westminster and the Public Service

12.1 Reforms to the Public Service by the Hawke government

12.3 Problems with Public Service and Westminster: disparities in power

12.4 Reforms to the Public Service

13.1 Compulsory voting

13.2 The importance of elections:

13.3 Elections in Australia: legal basis:

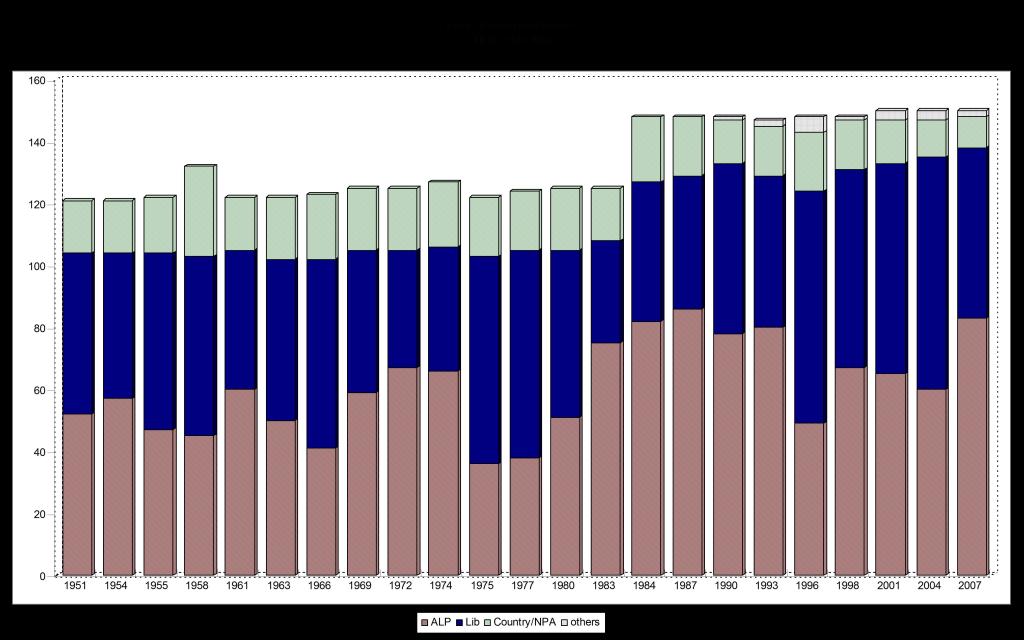

13.4 allocation of seats

13.5 The Constitution and elections

13.6 The Electoral Act of 1918

13.7 Electoral boundaries

13.8 Gerrymandering and malapportionment

13.9 Preferential Voting (Alternative Vote). Majoritarian systems

13.10 Electoral boundaries

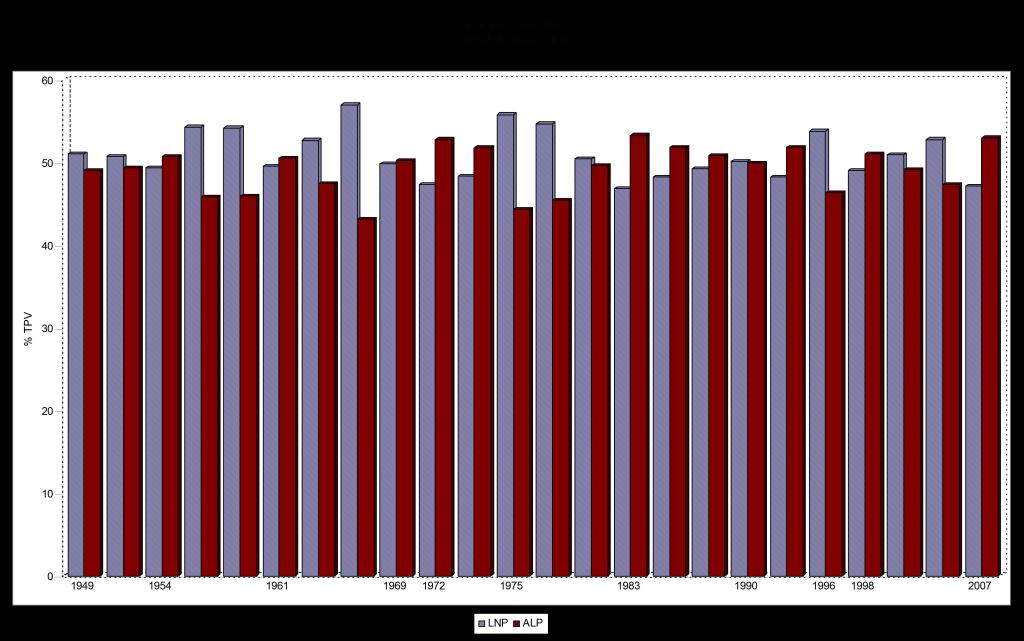

14.1 Preferential voting

14.2 How to count a Preferential Vote Election

14.3 Two Party Vote (TPV)

14.4 Counting preferential elections: McMillan – 1972

14.5 The two-party vote versus the primary vote

14.6 Proportional Representation

14.7 Relationship of Representation to Vote: Proportional Systems

15.1 The Senate system

15.3 Double dissolution

15.4 Hawke reforms – the Group Ticket Vote

15.5 Parties

15.6 How Family First’s Fielding won a Senate seat

15.7 Effect of minor parties on the major party vote

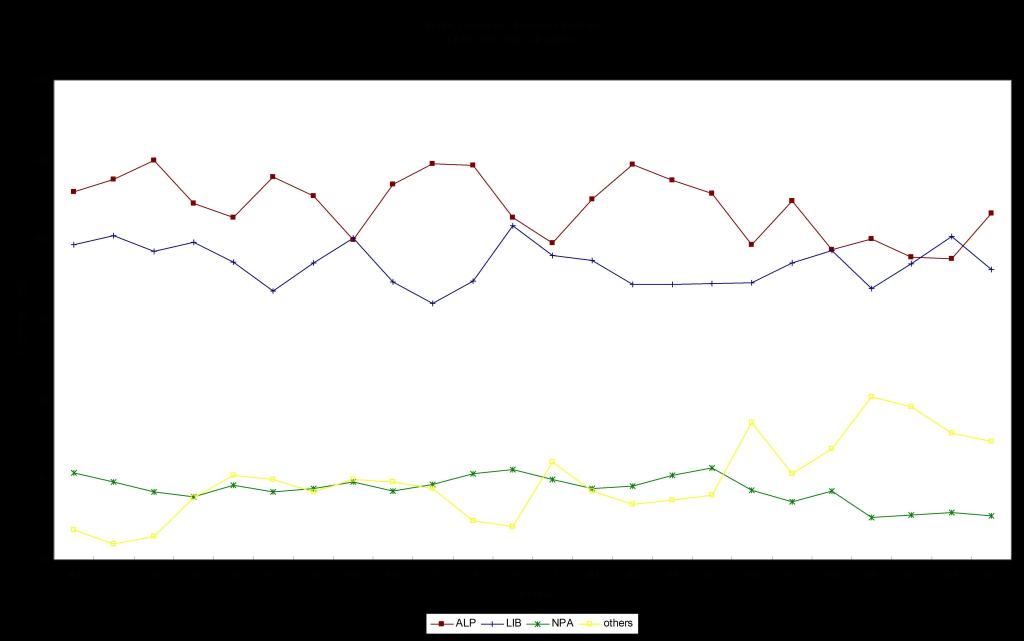

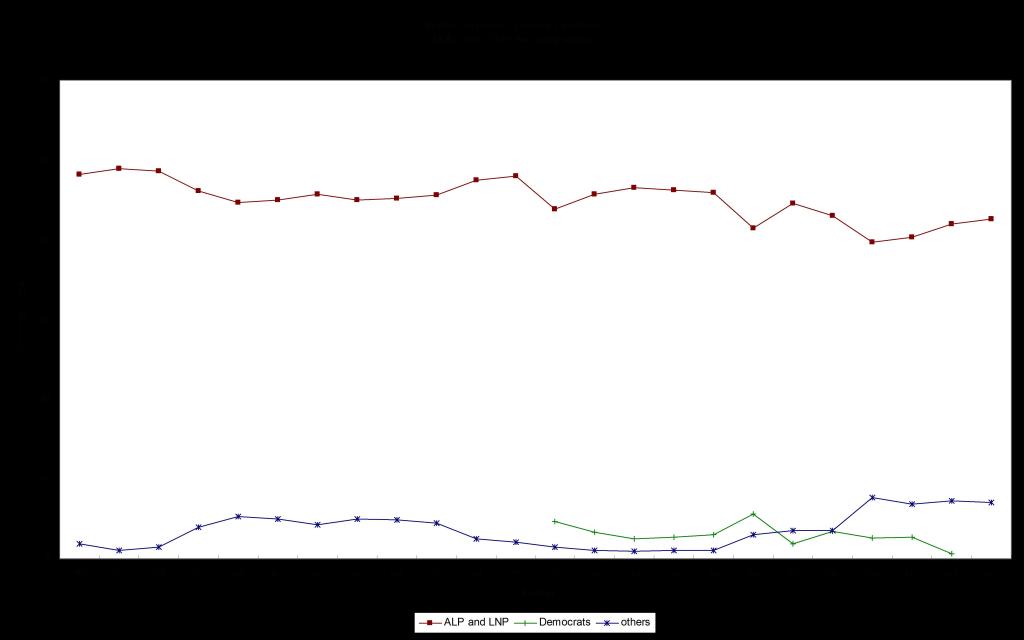

15.8 Electoral Behaviour

15.9 Voting Behaviour: Australian federal elections

15.10 Electoral behaviour and political sociology:

15.11 Social cleavage and the party system

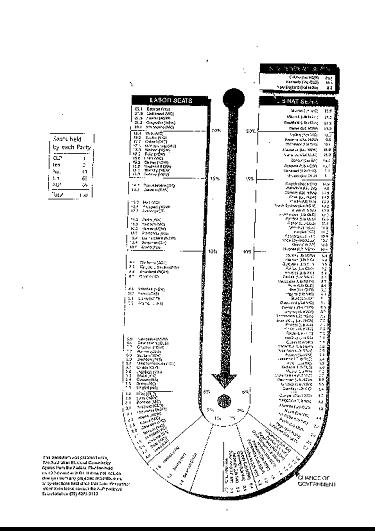

15.12 The Mackerras election pendulum

16.2 Definitions

16.3 Three party system

16.4 Constitutional references

16.5 Sartori on factions

16.6 Key functions of the parties

16.7 Recruiting individuals to the organisation

16.8 Policy debate

16.9 The glorious workers’ party – The Australian Labor Party

16.10 The Australian Labor Party – History

16.11 ALP origins; key dates

17.1 British election results – May 2010

17.3 The Australian Labor Party – organisational structure

17.4 ALP organisational politics: key features

17.5 ALP National Conference: evolution

17.6 Labor factionalism:

17.6 Labor and organisational politics

17.7 Labor and the policy debate

18.1 Labor – summing up

18.3 What does Labor stand for?

18.4 The Liberal Party

18.5 The Liberal party: main themes

18.6 Evolution of the non-Labor parties

18.7 The creation of the Liberal party: process

18.8 The Liberal party organisation: key points

18.9 Liberal party: growth, consolidation and success

18.10 The Liberal party and intra-party politics

18.11 Liberal Party: contemporary factionalism

18.12 The Liberal party: party ideas

19.1 The Liberal Party of Australia: Organisation

19.2 Geographic specificity – Free Traders v Protectionists

19.3 Affiliation of external associations

19.4 State Council and Federal Council

19.5 Federal and state directors

19.5 Party Room Meeting (aka ‘caucusing’)

19.6 Intra-party politics

19.7 division over philosophies

19.8 ‘wets’ and ‘dries’

20.2 Joh Bjelke-Petersen

20.3 Lower house seats

20.4 Balance of power

20.5 Coalition

20.6 Doug Anthony

20.7 Tim Fischer

20.8 One Nation and the demise of the NP in Queensland

20.9 The Country Party: origins

20.10 The Country Party and Preferential Voting

20.11 Practical outcomes oriented

20.12 State intervention

20.13 Beginning of coalition politics

20.14 Significant dates

20.15 Country Party – Labor coalition in Victoria

20.16 Evolution of the Country Party; National Party name

20.17 The Nationals and the electoral system

20.18 Regional specificity

20.19 Coalition agreement

20.20 Themes and issues in internal party politics

20.21 Themes and issues in internal party politics

20.22 The Difficult Years

21.1 General principles

21.3 Duverger’s Law

21.4 The ‘minor party’ system: some core themes

21.6 The green parties: WA Greens, Tasmanian Greens, the Greens

21.7 One Nation: a special case

21.8 Minor parties: some conclusions

21.10 The Democratic Labor Party (DLP)

23.1 Interest Group politics: overview

23.2 Interest group theory: basic themes

23.3 Interest groups: typologies

23.4 Interest group politics and political theory: the state, democracy and power

23.5 Theories of interest groups and power: Pluralism

23.6 Pluralism’s Critics

23.7 Interests Groups – Conclusion

1 Introduction

The USA was the first Liberal Democracy, followed closely by Australia.

The first form of Australian government was military (martial), autocratic, and hierarchic (Governor / soldiers).

By 1855 (marked by the end of ‘Transportation’), all the colonies (original states) had parliamentary government (Responsible Government).

The date of Federation was January 1st, 1901

The Civil Government was comprised of:

- Institutions:

1. Executive

2. Legislature (parliament – representatives)

3. Public Service

4. Judiciary (courts)

5. Military (Martial Law)

The three main themes covered by these lectures are:

1. Liberal Democracy

2. The Westminster System of government

3. Australia as a federation

2 Classical Democracy

Classical Democracy (Athens: 490BCE – 411BCE):

* Civic culture: Citizens involved in affairs of State

* Answerability and accountability of officialdom

* Citizenship as a social contract: rights in exchange for duties to state

* Direct Democracy – made possible by the small size of the population and occurred when citizens voted directly on matters of governance (rather than through representatives)

* Alternative to autocratic states

Examples of non-democratic states are monarchic states and ecclesiastic states (e.g. Iran).

Democracy breaks down the power of the elites.

Communism is an example of a one party state.

WWI marked the decline/collapse of monarchy (e.g. Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian, etc).

Mid 1600s:

* Beginning of rise of parliament as key institution of government in the Westminster system

* Beginning of battle between Parliament and the king for control of affairs of State (Britain)

So our system of government predates the rise of mass democracy.

Our current system is democratic because the right to vote (known as ‘universal suffrage’) was extended to men in the 1850s.

In many countries the idea of monarchy is antithetical to democracy.

In becoming democracies, many countries ousted their monarchy (e.g. Greece).

3 Modern Democracy

* in 1787 North America creates a system of democratic government

* Instead of monarchy, America has:

* a directly elected head of government – the President

* a directly elected parliament – the Congress

* an elected executive, and an elected legislature

4 Liberal Democracy

4.1 The Constitution

(is a legal document):

1. is a rule book for parliament (establishes mechanism for national parliament)

2. divides responsibility for government between national (Commonwealth) and State governments. Neither of these can dissolve the other

3. is a product of a combination of two isms:

a. Conservatism – half the contributors were conservatives, suspicious of change

b. Liberalism – the other half were colonial liberals

4.2 Revolutions

* France – the common people displace the aristocracy

* US – overthrow of British crown; democratic government

* Industrial – the rise of “mass politics’ and ‘socialism’

The Industrial Revolution:

* changed social relationships

* spawned :

o communism

o political parties

o trade unions

4.3 Liberalism

Liberals are about individuals. Socialists are about collectives.

Liberals are philosophically opposed to socialism and communism.

Our education system is based on John Stuart Mill’s liberal philosophy.

Liberalism goes hand in hand with ownership of private property.

Capitalism does not always go hand in hand with democracy; sometimes it is the opposite.

Elections are the foundation stones of Liberal democracies.

The Essence of liberal democracy:

* Constraint of powers – to protect individual rights

* Separation of powers

5 The Australian Constitution

5.1 Federations and Federalism

Federations occur where previously autonomous, self-governing units come together and agree to create a national (central) government.

i.e. the six colonies or ‘original’ states (SA included the NT).

NZ participated in the first Constitutional convention (1890s) but decided against joining the Federation.

5.2 Reasons for federation

- The six original colonies predate the national system of government

- After 1855 the colonies were effectively small, independent, autonomous, self-governing countries in themselves.

- They decided to create a central government

- They agreed to cede certain policy making powers to the national government

Initially the intention (in formulating the Constitution) was that the STATES would be the most important level of government in Australia.

However, contemporary Australians consider the NATIONAL level to be the most important.

5.3 Federation – defined

Federation (an indissoluble separation and redistribution of power):

- Systems designed to decentralise the power of government

- Two levels of government:

- national & sub-national (states)

- coequal power

- both have autonomy

- neither can dissolve the other

A Unitary system is one in which there is only one level of government – e.g. Britain, where Westminster has Parliamentary Sovereignty.

5.4 The Constitution – defined

The Constitution – a legal document – does 3 things:

- Provides the rulebook for operation of the national parliament

- divides the responsibility for government between the two levels of government

- The ‘Division of powers’ – (part of) a legal document

- The power to interpret the Constitution is put into the hands of the Judiciary (the High Court of Australia) independent of Politics – derived from the British notion of Separation of Powers: the Court is independent of the Parliament.

Altering the federal Constitution is no simple matter.

However altering the constitution of the States is fairly straight forward; It is achieved by passing legislation through the parliament – if the government has a majority in both houses, this is easily achieved (note that the upper house in state parliament is not elected in the same manner as in the national parliament and, therefore, might well be controlled by the government).

e.g. Queensland (alone, of the states) has abolished its upper house.

5.5 Changing the Constitution

To change the national Constitution:

- The bill needs to pass both Houses (not a simple matter if the government lacks control of the Upper House)

- It needs to be approved by referendum

For a referendum to succeed, two things are required:

- The proposal must receive a majority of votes

- It must also win in a majority of states

Out of about 47 or 48 referendum in the past, only 7 or 8 have succeeded and, for the best part, they were only minor changes.

NB the in-built protection of minority interests, i.e. the small states.

Small states (at the time of federation): Tassie, SA, WA, Qld. Big states: Vic, NSW

Note, at the time of federation, the rivalry between Vic and NSW (read Melbourne v Sydney) necessitated the creation of ACT / Canberra (otherwise federation would not have occurred!).

Canberra is the product of Federation.

Nothing has changed! (Tension between big and small states – Melbourne and Sydney).

At the time of Federation (Jan 1, 1901): The crucial time for the Federation movement was 1890 – 1900:

- series of constitutional conventions attended by premiers of the colonies, ministers of the colonies, attorneys general and lawyers, colonial conservatives, and colonial liberals

- already taken place has been a key transfer, based on the British model (not written), of parliament as a key institution of government

- there is great interest in American federalism

The American system of federation becomes a model for Australian federation (based on similarities in our circumstances, particularly states)

5.6 The American model

Borrowed American ideas:

- Courts: Supreme Court = High Court

- Parliament: Congress = Parliament

- Two chambers:

- Upper: Senate = Senate

- Lower: House of Reps = House of Reps

- Two chambers:

5.7 The Senate – defined

The Senate: A directly elected upper house that will represent the federating states

The Senate causes huge amounts of grief in blocking legislation. This remains a problem to this day. (e.g. the 1975 constitutional crises precipitated by the senate blocking passage of supply bills)

Note that the Senate is NOT an anachronism (as critics have argued) – it is a POWERFUL house.

Despite huge changes in politics, the statement that ‘the Senate is there to represent the federating states’ is as important today as it was in the 1900s. It underlies the following important principle (that of liberal democracy):

5.8 Liberal democracy – defined

Liberal democracy is the coming together of two potentially contradictory ideas:

- That government exists at the behest of the people – the House of Representatives

- That it has a chamber that represents the federating states – the Senate

5.9 Parliamentary Bicameralism

In 1855 – 1901, in the colonies, the prevailing view was that the upper house should be like that in Britain:

- Conservative view point – constraining the potential of the lower house for radicalism in law making

- a chamber to slow the legislative process, allowing conservative views to temper the potential for the ordinary people to make radical change

This view was transferred to the Australian Constitution (at least in intention):

- Upper house as a brake, a means of check and balance on the lower house; a conservative view

The liberals and the conservatives, together, share a fear of ‘mob rule’.

Overriding principles which were instrumental in the constitutions of the colonies (pre-federation):

- Government is formed in the lower houses

- it is constrained by powerful upper houses

- idea that courts are able to overturn things that the government do

All these precedents were replicated in the creation of the Australian Constitution

5.10 Separation of powers

NB: Important notion of Separation of Powers (colonies predate the national constitution)

The Legislature and the Judiciary shall be separate (and also the Public Service)

(For further detail refer to Section 11.7 Separation of Powers)

5.11 The Crown

The Crown is represented by the Governor-General

The national and state constitutions make NO reference to premiers or prime ministers or cabinet.

They go out of their way to describe the functions of governors or governors-general, but make no mention of premier or pm or cabinets. Why?

Because, as good ‘British’ citizens, we would understand Westminster Conventions, obviating the need to write them down – Britain does not have a written constitution.

The Executive-in-Council (equivalent to British Privy Council) technically rules Australia. This is the Governor in council with leaders of Parliament.

We assume (with the exception of Victoria – the only state to write it into their constitution) that when the Executive Council meets with the Governor, or Governor-General, that he or she will take the advice of the executive, and follow it.

This is because of the Westminster convention that the Crown will act on advice of the Parliament. This dates back to the 1600s and the fight between the Crown and the State. There is no legal basis, just slippery convention.

5.12 What the Constitution does

- establishes Australia’s head of government – the Governor-General

- establishes bicameral parliament, directly elected

- provides for Judicial overview

- outlines division of government powers

- provides financial assistance for the states

- provides for Inter State free trade

- provides the mechanism for altering the Constitution

5.13 Why federate?

- Defence – a national approach

- Immigration (external affairs, international diplomacy)

- Intercolonial free trade

[http://www.samuelgriffith.org.au/papers/pdf/Vol17.pdf – Upholding the Australian Constitution Vol 17]

6 The Westminster System

Recapping to date:

The 3 Big Statements:

- Australia is a Liberal democracy

- Australia is a federation

- Australia is a classic example of a Westminster system of government

We are a Modern Representative Democracy: (Joseph Schumpeter definition)

- We have popular sovereignty – those who govern us do so with our consent

- we have attained consent through the electoral process which enjoys popular support

- we are a liberal democracy, with many constraints on the power of government

- the whole point of liberal democracy is to have a balance between the rule of the majority, and the protection of minority interests. The liberals are concerned about the “tyranny of the majority”.

6.1 Constraint of powers

Our system is full of mechanisms designed to constrain the power of the state.

We have a federal system with two levels of government: National government in Canberra, and state governments.

6.2 State and national constitutions

There are many constitutions:

- each state has a constitution

- there is a national constitution

Most important features of the national constitution:

- Provides rules and regulations for operation of the parliament

- Provides for the Division of Powers between the two levels of government: S. 51 of the Australian Constitution divides powers – Exclusive; Concurrent; and Residual.

6.3 Westminster System

Unlike the Constitution, there are no written rules; no legal documents. There is a raft of opinions dating back to the 1700s.

The Australian Parliament has two major tomes, published by the two houses; guidelines for MPs on how the Westminster System operates.

There are lots of academic texts, but no constitutional rules for the Westminster System.

The essence of Westminster government revolves around the primacy of Westminster conventions. Conventions are very important to the operation of the Westminster System.

Conventions are unwritten rules of a constitutional practice. They are accepted, traditional, customary procedures for the operation of parliaments, and for the operation of parliamentary governance.

6.4 Executive-in-council

Constitutionally, the Executive-in-Council consists of the PM and the Governor General in Canberra, and the Premier and the Governor in the states. This is the formal mechanism of government.

But the convention is that the Crown (in the form of the Governor or the Governor-General) does not run the state, the Premier or the Prime Minister does. The Crown only acts on the advice of the Prime Minister.

6.5 Conventions

There are heaps of minor conventions, including many anachronistic curiosities. For instance, when the Speaker (which is a favoured position of privilege) is elected, he feigns reluctance and is dragged to his new position by the MPs at his side. (This reflects the historic reality that he was liable to be beheaded when conveying unfavourable advice from the parliament to the monarch). Another instance is the presence of the parliamentary mace, which used to be used to control unruly members. These things serve as reminders of the origins of Parliament.

Conventions can evolve.

The system has evolved for over 300 years.

Written rules are fixed, but not conventions.

[following a recap of what the Constitution does …]

6.6 S.96 – Financial assistance for the states

S.96 allows the federal government to make payments to the states on terms and conditions outlined by the Federal Parliament. Therefore S.96 allows Federal Parliament to make policies in areas it was never intended to legislate on.

We are in a S. 96 environment now (the university) – it was never intended for federal government to run higher education. It was intended that higher education be run by the states. But everything that goes on in the uni is paid for by the federal government, through S. 96. Note also that the federal government is currently taking control of health, using S. 96

S.96 gives the government great financial power.

6.7 S.92 – Nationalisation

You cannot have socialism in Australia, at a federal level, because, in 1947, the High Court of Australia held that S. 92 does not allow the federal government to nationalise an industry.

At that time the federal Labor government tried to nationalise the bank of NSW. They were trying to turn the privately owned bank into public ownership. The legislation passed through both houses, and the Governor-General gave it Royal assent. But then the bank took it to the High Court of Australia, and, in 1947, in one of the most celebrated of High Court cases, they held that S. 92 did not allow for nationalisation.

S.92 is an important constraint on the ability of governments to govern. i.e. Liberalism par excellence!

State Labor governments CAN nationalise – there are no constitutional constraints on nationalisation by state governments. For example, the hydroelectric company, in Tasmania, which no longer exists, was originally private, before it was nationalised…

6.8 Constitutionalism

The difference between Constitution and Constitutionalism:

- A constitution is simply a written document

- Constitutionalism is understanding the written document against the backdrop of Westminster – the culture, the practice, the conventions.

When you talk about Australian Constitutionalism, it is not sufficient to simply read the written document – you must understand the Westminster context as well.

Important constitutional creations:

Bicameral parliament:

- Lower House: House of Representatives – three year terms

- Upper House: the States’ house – six year terms.

6.9 Upper house tenure

Upper house MPs are deliberately meant to have twice the tenure of lower house MPs. Why?

Because the constitutional framers wanted to create a Senate that would not be under control of the PM

i.e. a mechanism to put a brake on the lower house and the power of the prime minister.

At a normal election, all of the House of Representatives go to election while half the Senate go.

The constitutional framers deliberately wanted the Senate to be a pain in the arse for the House of Reps.

6.10 S.53 – The Senate and tax bills

S.53 is a very interesting section which says that the two houses of parliament are coequal in power, with one important exception. It says that the Senate may not initiate Tax bills (laws / legislation). This is one instance where the Constitution does codify (commit to writing) the Westminster convention. It further says that tax bills may not be amended by the Senate.

Just because the Constitution says the Senate can’t initiate or amend, does not mean that they can’t REJECT tax bills. (This is not mentioned in the Constitution). It is a Westminster convention that, if a government can’t get its taxation bill, and its supply bill (the law authorising the provision of government money), through the parliament, they are considered to be defunct and should resign.

The Australian Senate has the power to force the lower house to an early election by rejecting supply.

This is also the case in every Australian state except Queensland (who have abolished their upper house), and Victoria. The Victorian constitution says that the only house that can vote on a tax matter is the Legislative Assembly. If the Legislative Council were to block the bill, the Premier would go to the Governor and say that the bill has passed the lower house and advise him or her to give consent, after which he or she would comply. The lower house is the house of government. In this way Victoria is different to all other states. This was the result of a 2003 amendment, prior to which it was the same as all other upper houses, with the right to refuse supply and force an early election.

6.11 S.57 – The double dissolution and joint sitting provision.

Also known as ‘the deadlock provision’.

S.57 provides a solution to a dispute between the two houses of parliament.

- The government introduces a piece of legislation which is rejected.

- After 3 months the bill is returned to the Senate

- If the Senate rejects it again, the constitution says that the Governor-General may dissolve both houses of parliament and call a double-dissolution election. [There is no reference to the prime minister. In Australia we use the convention that the Governor-General only uses this provision if so advised by the PM. Section 57 is a mechanism for use by the PM]. At this point the prime minister can take all the twice rejected bills to the Governor-General and request that he issue writs for a double-dissolution election.

- If the government is returned after the double-dissolution election, it has the right to re-introduce all those twice defeated bills to a joint sitting of the parliament – both houses sitting as one.

- Because, by constitutional order, the House of Reps is twice the size of the Senate, and the government must control the House of Reps, they will probably succeed with these bills.

- We have only ever had one joint sitting in 100 years of parliament, in 1974. Amongst those bills presented was the one that allowed the NT to vote in referendums. Also that which allowed the NT and the ACT to have Senate representation (the people of the NT and ACT had previously had no representation in the Senate).

- Some of the bills that were passed in that joint sitting were later rejected by the High Court.

6.12 S. 5 – The role of the Governor-General – Reserve Powers

There is an argument to be made that the G-G and the state governors are more powerful than the Queen, because there is an expectation, almost a conventional expectation, that if there are going to be major political disputes, especially disputes between upper and lower houses, somebody has to be able to deal with the dispute. That somebody is the governor or the Governor-General.

The principle of the governor, or the Governor-General, intervening in a dispute “to preserve government” is sometimes referred to as ‘Reserve Power’:

The principle that the vice-regal heads of State have an obligation to preserve good governance of the Australian colonies, and that they should intervene in the case of a dispute.

Most liberal-democracies have a head of state, a President, with a residual power; that they can become the final avenue of appeal; to be the final resolver of a fundamental political dispute.

6.13 What the Australian Constitution does NOT provide for

It does not make any reference to the Westminster System. Why not? They debated it in the constitutional conventions in Bendigo (read about it in the Collected Works of Quentin, Quick, and Garran – the Annotated Australian Constitution), so why not write it down?

“Is there any need delegates?” “No, there is not. We are all good Britishers together – we understand how the Westminster System works”.

The constitutional framers deliberately avoided writing it down. Why? Because Britain does not have a written constitution. It does not have a single document that outlines the constitution. They have a range of laws, conventions, and practises. So the feeling was that we don’t have to do that in Australia. The primary reason for the Constitution was to divide powers between the Commonwealth and the states.

It makes no reference to cabinet government, or to the prime minister, which is a terrible omission as both are crucial to government in the Westminster System.

There is no explicit declaration of citizen’s rights – we don’t have a Bill of Rights. Liberties are assumed to be covered by the common law (transferrable British common law).

There is no reference to Party Politics, with the exception of S. 15, which was amended by referendum in 1977. (S. 15 is the amendment to the way in which casual Senate vacancies occur).

Some of the key features of what we consider to be at the core of Australian politics – cabinet government, the prime minister, party politics – are not in the Constitution.

6.14 No Parliamentary Sovereignty in Australia

In Westminster the British Parliament can legislate on whatever it likes, only constrained by politics (what it can get away with at the next election). This is not the case in Australia where the national parliament cannot legislate on whatever it wants. It is constrained by S. 51 of the Constitution, and it is constrained by the High Court of Australia. If the High Court of Australia decides that what has been legislated is outside the Constitution, it will nullify the legislation. Ask Ben Chifley.

7 The Westminster System – part II

7.1 Responsible Government

- Government is answerable to the parliament

- Parliament is answerable to the voters

Responsible Government is measured by two things:

- Does it have a majority of support in the lower house?

- (The government must come from the lower house)

- That a government can get its budget and supply bill through. Budget = tax + supply. Supply is the legal authority for the government to spend money – very important.

If you are no longer a Responsible Government then, by Westminster convention, you must advise the Crown and resign or, in the case of Australia, expect the Crown to sack you. If you are the premier or prime minister, you should go to the governor, or governor-general, and say “I can no longer govern. I advise you to call on the leader of the opposition to see if he or she can form a government. If they can’t form a government then let the voters decide”.

[In response to a student’s question as to whether the government could call a double dissolution to resolve the deadlock, Nick answered as follows:

S.57 is not really meant for a budget. It’s intended for ordinary bills. Between 1996 and 2004, Howard’s government, with the Democrats holding the balance of power in the Senate, tried to pass unfair dismissal legislation 27 times. So just because it’s rejected twice doesn’t necessarily mean a double dissolution must follow. by convention it’s one of those sneaky little powers that the PM can use. (And it was highly unlikely that Whitlam would have won an election at that time. As it was, when a double-dissolution election was held shortly afterwards, the Fraser government had a land-slide -my own note). What makes 1975 so controversial is that the Governor-General used section 57 without the PM having advised him to do so.]

Also associated with Responsible Government are other forms of answerability:

Ministerial Responsibility:

Government is made up of Ministers of the Crown. These are members of parliament who have been sworn in by Her Madge, in Britain, or the Governor-General in Canberra. They usually come from the side of politics that has the majority of seats in the lower house. Westminster systems lend themselves to party politics.

Even by the 1700s, in Britain, party politics – groups of people who band together to make political parties – were coming though. Today is a bit different: we have ‘rigid discipline’ parties. Currently we have three in the lower house – Labor, Liberals, and Nationals

The party with the majority of seats forms government. The leadership group (leader, deputy leader, etc) of that party becomes the Government. We do not vote for a PM directly (he or she is only voted for directly by their own constituency). We vote for parties. Westminster systems are dominated by disciplined political parties.

Who becomes Prime Minister? The leader of the party that wins the majority.

The difference between the Ruddmeister and Abbot:

they are as

- smart as each other

- Catholic as each other

- conservative as each other

- dull as each other

The only difference is that Rudd leads the Labor Party and Abbot, the Liberal.

The cabinet will be the senior ministers. The leadership will be invested with the power and authority to be Ministers of the Crown. Under the Westminster system this means they get to do two things:

- They get to initiate policy:

- A minister is given a ministerial portfolio. Portfolios are usually divided along specific government funding lines: e.g. Treasury, Defence, Education, Health, etc.

- They become responsible for the Public Service department that manages that portfolio. If something goes wrong the minister is responsible. If there is a breach of Ministerial Responsibility, by Westminster convention, a minister should resign or expect to be sacked by the prime minister.

Ministerial Responsibility is a form of answerability

The Government comes from the Parliament. To survive it must first win an election. It is then considered ‘Responsible’ as long as it commands majority support in the popular house – the lower house, the House of Reps / The House of Commons.

(House of Reps is the one decked out in green.)

2 or 3 important points: It is not uncommon for a government to lose the vote on some pieces of legislation. This is especially so in parliaments where the numbers are very close in the lower house.

So the doctrine of Responsible Government focuses primarily on:

7.2 Appropriation bills

- The fate of budget legislation, and in particular the bills that go through a parliament that authorise government expenditure, technically called ‘appropriation’ bills – bills of parliament that, once passed, will become law, enabling the government to pay for things, such as the army, universities, police, etcetera.

Under Westminster, if a government can’t get its appropriation bills through the parliament it is no longer ‘Responsible’ and should expect to go. It should either resign or expect the head of state to move it on.

In Britain, if the government can’t get its appropriation bill through the House of Commons it would be in a political crisis – it would no longer have the numbers in the House of Commons – and the PM would then go to her Maj., resign, and ask her to invite the leader of the opposition to see if they could form a government. If he or she replies that they can’t then, by Westminster convention, the House of Commons will be dissolved and have a fresh election.

The bottom line is that if there is a doubt about Responsibility, it must be resolved by the People. But this must happen via the process. The Crown first checks with the Opposition. This is because of the principle that all possible avenues (from the last election) must be explored before proceeding to a fresh election. This is straight forward in Britain because only one house is directly elected. It is complicated in Australia because we also have an elected upper house.

The possibility of not getting appropriation bills through Australian Parliament is real.

This is all the more so if, as is almost always the case, the government of the day does not control the Senate.

7.3 Motions of no confidence

- If the Opposition moves a motion of no confidence against the government, and it succeeds, the government would no longer be ‘Responsible’ and would have to resign.

If the Rudd government tries to get a health bill through and is defeated, it doesn’t mean that we should go to election. If they can’t get a budget through, it’s different – a crisis. Then there’s a problem as to whether it is a ‘Responsible’ government or not.

The electoral process is important, but so is what happens in the lower house.

How could a motion of no confidence succeed?

Here’s a hypothetical example:

Tasmania has elections resulting in the election of 11 Liberals, 10 Labor members, and 4 Greens. The Greens, therefore, have the balance of power.

The Liberals secure the promise of the Greens to give them support (or to form a coalition) and so ensure a majority. Whenever bills are presented the Greens support the Libs and the bills are passed. However, a year or so later the Greens tire of the Libs and promise the Labour Party that they will withdraw their support for the government. Providing the Labour Party agree to certain Green concessions, they will oust the Liberal premier.

In the next session of the Tasmanian lower house, the Labor leader asks the Speaker to suspend Standing Orders, as he wants to move a motion of no confidence. The Speaker, being a Liberal, refuses. Consequently, there is a division. The four Greens vote with the ten Labor members. 14 is a majority in a 25 seat house. Then follows the motion of no confidence, which is carried. What happens next is NOT a fresh election. Next, the former premier, just defeated in the house, goes to the Governor and says “I no longer have the confidence of the house; my advice to you is to call on the leader of the Opposition to ask if they can form a government. The Governor complies, the leader of the Opposition replies in the affirmative, and the government changes, even though there has been no election.

This can happen. It is very rare in national politics because the House of Reps is so large that, with the preferential voting system, it’s rare for the Government to be in a minority position. But it did happen between 1939 and 1942. In 1939 the United Australia Party had a minority government. There were two Independents, who supported it. (Joe Lyons was PM – he died in office and was replaced by Robert Menzies, when he was a young smart-arse from Melbourne uni – not really liked in the UAP, but their best and brightest. He had a terrible time of it cos half the party people disliked him; they ending up just arguing with each other. And in 1939 there was a bit of a problem happening. It was WWII and the Japs were actually bombing the joint. So a major problem developed. The two Independents said “Bugger this” and crossed the floor – went to the cross-benches and supported Labor. That was how John Curtin became the first war-time Labor PM, even though there was no election.

It can happen sometimes: a Government changes without an election. It’s simply a reconfiguration of the numbers on the floor of the lower house. It doesn’t happen often in the national government. That described may well be the last time.

The UAP was the forerunner of the Liberal Party. If you understand why half the UAP didn’t like Bob Menzies, then you are half way to understanding the internal politics of the Liberal Party. They still haven’t got away from it. (Melbourne – Sydney tension).

Bob Menzies didn’t lose the leadership of the UAP (contrary to the ramblings of some political journos). He said “I’ve had enough of this”, and resigned, and the Country Party took over. (When the Country Party – now Nats – takes over, we’re in big trouble. It also took over when Harold Holt disappeared. Bob Menzies resigned. Political journos said “Menzies – what a dud. We’ll never see him again”! He later became the longest serving Australian PM.

7.4 Ministerial Responsibility (recap)

It is Westminster convention that when you become a Minister of the Crown you must be part of the Government.

The Government is made up of ministers – sitting on the Speaker’s right, on the front-benches.

The Minister is responsible for policy, and is in charge of his or her Public Service department.

There is a price to be paid for ministership, being part of the Executive, having a position on the front-bench: if something goes wrong you are expected to take the blame – full responsibility – you should resign. [The Westminster system is a Winner takes All system. An adversarial system – there are Shadow Ministers to match the Government Ministers, but Opposition is worth nothing. When they take the floor, everyone yawns. They have nothing to do but change their leader.]

The Public Service is a really important part of Government. Those hopeless in Opposition can become apparently brilliant in government.

e.g. Paul Keating: Lots of Labor luminaries still love him. But (in Nick Economou’s opinion) he was an unmitigated disaster. He suffered one of the worst defeats that Labor has ever experienced. A couple of Labor leaders that have really copped it: Herb Evatt copped it when he lost his marbles. Arthur Caldwell copped it when he opposed the Vietnam war, at a time when everyone favoured bombing Vietnam back to the middle-ages. Gough Whitlam copped it in 1975 and ’77. But Paul Keating copped it too – so he was a disaster.

Paul Keating is often considered one of the greatest treasurers Australia has ever had. Peter Costello is often said to be the greatest treasurer we’ve had. Costello was a law student. He was a minor solicitor of some sort in an industrial relations case. Paul Keating left school at 15. His only job, before being elected to parliament at the ripe old age of 23 or 24, was managing a rock band in western Sydney. Ugh. Imagine what that would have been like (the band). He had no idea. He was never trained in Economics. So how do these guys become so brilliant? Because their Public Servants make them so. They are a crucial part of government.

It is important to be a minister.

It is important to be in charge of a ministerial department. The double-edge of the sword is that if something goes wrong in your department (Mr Garrett and insulation?) the Westminster convention is that you should resign. However it doesn’t happen that way in practice. This is an instance where ‘party politics’ intervenes and mitigates a Westminster convention. It is not often that a PM will stand in front of Parliament, or a community, and say “my minister’s a dud. He’s been responsible for the burning down of several houses in Queensland, and I’m sacking him”.

How would the Herald-Sun report Mr Rudd sacking Peter Garrett on the grounds that he’d stuffed up the insulation program?

Would it be (next to a picture of Nick Riewoldt on the front page) screaming headline:

GARRETT STUFFS UP. RUDD SACKS GARRETT. ALL IS WELL. WESTMINSTER RESPECTED ?

No! More like:

RUDD STUFFS UP. RUDD SACKS GARRETT. GOVERNMENT IN CRISIS

PMs and premiers know this, so they tend not to apply the full letter of the law.

It is both attractive and annoying (to the lecturer), about the Westminster system, that there are all these conventions that provide behavioural benchmarks – this is the way the thing is supposed to work – and that they are never really met, and one of the reasons for this is because disciplined party politics intervenes.

A PM, or premier, with someone like Garrett, will defend him. Rudd has defended him all year, first by saying nothing, then by shilly-shallying, and finally, the ultimate: “it was my fault, says the PM”. So the Westminster convention is not respected, but we need to know that it’s there because it’s a benchmark of behaviour; a standard.

Ministerial Responsibility is very important because it has important implications for the complicated relationships between ministers and the Public Service, a very important part of modern government.

[Westminster primer seminars are provided to them because…] We find these days that so few Public Servants have done first year politics that they have no idea what a Westminster Public Service is. They have never heard of Ministerial Responsibility and they don’t even know how Parliament works. Yet they are considered to be a vital part of the system.

7.5 Collective Responsibility

Westminster convention says that when you become a member of the ministry (part of the government) you are bound by the decisions made by your colleagues.

In other words, decisions made when the full ministry meets (which is not very often) or when the Cabinet meets (which is frequently). Premiers and PMs will select half of their ministers to be Senior Ministers and they will meet all the time – these Senior Ministers are known as the Cabinet.

7.6 Cabinet

Cabinet is made up of half the ministry – the Senior Ministers.

When, occasionally, the Premier or the PM has a meeting with all the ministers, it is called a meeting of the Full Ministry. Whether it is a decision from a cabinet meeting or a full ministry meeting, all ministers are bound to that decision. They are bound to agree to the collective decision. Ministries and Cabinets can sometimes disagree about decisions – they will argue between themselves – but once a decision is made, all ministers are bound by that decision. If, as a minister, you cannot support the collective decision, you must resign, or expect to be sacked by the PM or premier.

We have had past instances of this, particularly during the Hawke years:

The federal government has constitutional power for airports. When the Hawke government had to grapple with the issue of a building a new runway, for Sydney Airport, abutting working class suburbs, all of which were represented by Labor MPs, and some of whom were in the Ministry, a couple of ministers disagreed with the decision to go ahead with the new runway, and resigned from the Ministry as a consequence. They felt they had to be able to go to their local constituents and say they supported them in opposing the new runway. But this is rare.

So

- You are bound by collective decisions

- This is a doctrine that allows for secrecy in government

[This is contrary to our democratic instincts, which would seem to require open government.]

The Westminster assumption is that in order to make a good decision, the government needs to be able to argue amongst itself about policy, but this is only possible if the decision making process is made in camera.

7.7 Cabinet secrecy

The Westminster system bestows secrecy on Cabinet, and ministerial, decision making.

You are a minister and you come out of the office. You ring Glen Milne; he’s not in his office – he’s at the bar! You ring Laurie Oakes, or Paul Austin, or whoever. You say “this is what happened in Cabinet, Laurie, mate; he said this… and that…” If it is discovered that you have had this conversation you will be sacked for breaching Collective Responsibility. Technically, you should never talk about decision making – EVER.

The High Court of Australia has found that cabinet documents, that is papers given to ministers, from their departments, helping them make decisions on policy, are also confidential. Under Australian Law they cannot be released for 30 years.

Public Service – The Westminster Public Service is a separate body. (Separation of Powers)

7.8 FOI

[In response to a question from a student re freedom of information act]

It’s a piece of legislation that has been put together to try to get around the problem of Collective Responsibility. When in opposition, Opposition leaders are fervent supporters of FOI. They know there’s something wrong somewhere… BUT remember the Westminster system: When in Opposition you have no contact with the Public Service whatsoever. There is one body only to whom the Public Service is answerable: NOT the Parliament; not the Press; not the Courts. ONLY the Ministers (in theory). Oppositions don’t like this – they want to know what’s going on. They use the liberal-democratic argument to justify reform. When we get into government we’ll bring in FOI – everything will be open… But what happens in practise?

[Ted Bailleau, now] What about FOI, Ted? I’m in favour! Sure you are. Are you really? – Just like Jeff: In Opposition, he was going to open everything up. But when he became Premier, getting information was like trying to get blood out of a stone…

One of the benefits of government is that you’re entitled to make decisions behind closed doors.

- Conventions are crucial to the operation of the Westminster system

- relationship to the Crown: the bottom line is that it only acts on the advice of Ministers – the PM or the Premier. The assumption being that the Parliament is sovereign, and that the Premier, or PM, is the head of government.

- Westminster parliaments are bicameral:

- they have a (popular house) lower house – the house of Government

- they have an upper house – the house of review

7.9 The Westminster Model

The Crown is linked to the Executive. The Executive is linked to the Parliament. The Parliament is linked to the People.

Professor Hugh Emy calls the model of Responsible Government a system of answerability and accountability. The whole thing is democratic because it is held together by each level being answerable to the level below.

The parliament is the most important institution in the Westminster system.

7.10 Westminster Cabinet

In a Westminster system, ministers of the government are Ministers of the Crown, who must be Members of Parliament.

The head of Cabinet is the Prime Minister or the Premier. Under Westminster there is an assumption that the PM is ‘first among equals’ in his or her cabinet. There is no pecking order. But this is not how it operates in the real world where the PM is very powerful.

The Cabinet = Senior Ministers of the Crown, sometimes called Senior Cabinet, or Inner Cabinet – they are the Government.

Cabinet initiates policy – parliament debates policy.

- Isn’t it true that MPs can initiate legislation? Private members bills; conscience voting?

Of course they can. BUT nothing will happen if the Cabinet doesn’t agree. A private member can pass as many bills as he or she would like but if Cabinet says ‘we are not going to consider them’ then they are howling against the moon, farting against the wind, wasting everybody’s time.

Sometimes private member’s bills get up. Sneaky PMs say ‘that’s a controversial thing, with which I kinda agree, but gee, it will divide my cabinet colleagues. I know what I’ll do – I’ll get some dork back-bencher MP to do it. That way if it goes down in a screaming heap, it will forever be known as ‘the Kevin Andrews euthanasia bill’ – hypothetical. (In this case it actually got through). (Kevin Andrews was rewarded by being made a minister – and a fair-minded minister, too!)

The same with conscience votes. Why do conscience votes happen? Because the Government allows them to. Who decides what will be a conscience vote and what won’t be a conscience vote? The PM. Cabinet dominates the process because of the connection between ‘part politics’ and the way Westminster parliaments operate, but it can use party discipline to force the issue.

The assumption is:

Cabinet initiates policy – Parliament debates policy, and Cabinet must have the confidence of the Parliament to govern.

7.11 Westminster – the Australian approach

- applicability of Westminster conventions

- At the centre of government is the cabinet, and the PM is the head of government

- We have bicameralism, but we have a problem with an elected upper house

- The British Parliament is a sovereign parliament but the Australian Parliament does not have parliamentary sovereignty: It can’t legislate on whatever it chooses; it is constrained by the Constitution, especially Section 51. If it steps outside of the constitutional authority, the High Court will raise the off-side flag.

- We have a written constitution that tries to bring Westminster and federalism together. (Some writer describes our system as Washminster).

- Contradictory conventions – our written document makes no reference to the PM but is full of references to the Governor-General.

7.12 The Australian Model

Section 61 says that the Crown – the Governor-General – is the head of government. (position currently held by Quentin Bryce).

Section 62 talks about the Executive in Council. It is a ritualistic body – just a symbolic ritual for the PM to meet with the Governor-General and the Executive in Council and say ‘Your Excellency, please approve these things that your parliament has done’.

The Government – the PM, the Cabinet, and the Full ministry are drawn from both houses; the House of Representatives, and the Senate. You can have a Senator as PM. There are no constitutional constraints to a Senator being PM. The main reason that it doesn’t happen is basically political. If you don’t control the Senate, every day would begin with the Opposition moving a motion of no confidence against you in the Senate. How soul destroying would that be? They couldn’t get anywhere. The Senate can pass no confidence motions until the cows come home, but the house of government is the House of Reps.

8 The Dismissal – 1

‘Fundamentals in Dispute’ – Hugh Emy’s description of the 1975 Constitutional crisis.

8.1 The 1975 Constitutional Crisis – 11 November 1975

It’s important to get a sense of the political debate at that time for a couple of reasons:

- to get a feel for why this was such a dramatic period in Australian politics

- to try to sort out some of the confusing issues associated with the 1975 crisis

It was a crisis in the working of the Constitution, arising from the fact that we, as a nation state, have not resolved one of the ‘fundamentals in dispute’ with our system. That fundamental is in whether it is possible to bring together a Westminster system, based on the notion of parliamentary sovereignty, and a federalist system. And the Australian experience of 1975 would suggest that it is not. But we still haven’t resolved the problem.

At one level the ’75 crisis is a simple problem, the essence of which is found in S. 57 of the Constitution – that is that there was an unresolvable deadlock between the two core institutions of our system – the Senate and the House of Reps. A fundamental piece of legislation – the appropriation bill, also known as the Supply bill, was blocked. Gough Whitlam’s Labor government had a majority in the House of Rep’s where the bill passed without any problem. But when it went to the Senate, which was not under Labor control, they refused to consider it.

The Whitlam Government could not get its appropriation bill through the Senate.

What the Senate had done was a little bit tricky. We’re aware that S. 53 says that the Senate can’t initiate or amend budget bills, but the Senate didn’t do either of these things. But it didn’t even reject the bill. (The High Court of Australia has, in the past, been asked to look into the Senate’s power to reject Supply, and has decided that the Senate can reject Supply if they so choose. What would happen then? Presumably the Government could send it back 3 months later and, if defeated a second time, presumably invoke S. 57, or, perhaps the PM, on hearing that the Senate is not passing the Supply bill, would opt to go to the G-G to request the Parliament be dissolved.

But what the Senate did in ’75 was to refuse to consider the bill.

It was a procedural motion. They refused to debate it – they would not allow the first reading of the bill.

8.2 How Parliamentary legislation is made

Standard procedure – the way modern Westminster parliaments, dominated by disciplined political parties, operate:

[The government of the day knows it has a majority in the House of Reps; the cabinet knows it can get its legislature through the lower house. The situation in the upper house may be a little more tricky.] A parliamentary bill begins as a decision in Cabinet or the ministry. Cabinet will decide what its policy will be. It will then instruct the Public Service to draft the necessary legislation. The Public Service (Attorney General’s department ?) drafts the legislation. Then the minister responsible (e.g. if it’s health policy it would be Nikola Roxon) will introduce the bill to Parliament. The first reading is undertaken by the Clerk of the Parliament, by simply reading the title of the bill. It then goes to the second reading. The second reading is where the responsible minister will outline the Government’s reasons for bringing the bill and the shadow Minister will outline the Oppositions position. This is the important reading – the one to pay attention to if you want to understand where the government is coming from.

The bill then goes to the committee stage. At committee, all the members of the parliamentary chamber (the House of Reps) attend. They debate the bill, clause by clause. They will vote on each clause as they go by. This is the time when the Opposition can move amendments to the bill. Of course this has no great consequence as the Government has the numbers. Sometimes the Opposition will try to stall the process by saying ‘here’s some amendments’. But, having the numbers, the Government can suspend all this. They can ‘railroad’ or ‘fast-track’ stuff through. They can apply what’s called ‘the guillotine’ – stopping the debate and getting the thing rushed through the House of Reps.

Another thing that can happen is that the Government can allow the bill to go to the House of Reps Standing Committee, where it would be looked at in detail. Most House of Rep committees aren’t particularly important as they are controlled by the Government. Where the committee system gets interesting is in the upper house, the Senate, because the Government doesn’t control proceedings there. Once the bill is approved at Committee, it then passes to the second chamber – it goes to the Senate for review.

This is where it gets tricky as the Government rarely has the numbers. If the Government do control the Senate (as Howard did after 2004), then the same ‘rubber-stamping’ exercise as occurred in the lower house, repeats in the upper house.

In recent times the Senate has been a benign institution; the likes of the Australian Democrats (R.I.P.), and Independents like Nick Xenophon, and Stephen Fielding – jolly good chaps that they are – may or may not pass things; may or may not do a deal, negotiate. But in 1975, Mr Whitlam faced a hostile Senate, controlled by the two major non-Labor parties – the Liberals and the Country Party (the coalition). This was where the problems started.

The situation for Rudd, Howard, Keating, and Hawke, was very different to that faced by Whitlam. Hawke, Keating, Howard, and Rudd have all dealt with Senates where minor parties held the balance of power, and were able to negotiate, so the Senate has been seen by this younger generation as a benign institution; an institution for good, constraining the power of the Executive. Mr Whitlam didn’t have the option for negotiation; he was against the Liberal and National parties, who would vote NO to everything – bloody-minded obstructionism.

When the bill goes to the Senate the process begins again – the Clerk of the Senate gives the first reading. Then a minister in the Senate, representing the responsible minister (e.g. the minister representing the health minister in the Senate – maybe Penny Wong?), will give the second reading speech, which is usually the same as the speech which was given in the House of Reps. Then it goes to Committee. Committee in the Senate is a tricky one because the opposition parties will hold the numbers. This is where the Government will negotiate with the minor parties and sometimes the minor parties will move amendments; the government will agree to the amendments and the bill will pass.

When the bill is amended by the Senate, a couple of things can happen:

First, it goes back to the House of Reps as amended. If the House of Reps accepts the amended bill (they vote and say ‘yep’), the bill goes to the G-G, at the Executive-in-Council, gets approval, and becomes law. If it fails, three months elapses, and it fails again, then S. 57 may be invoked.

Important thing to remember here:

8.3 S.57 Australian convention

By Australian convention, even though the Constitution doesn’t mention the PM, and, in S. 57, it says that the G-G has the right to invoke S. 57, the Australian convention is that it’s the PM who decides when S. 57 should be used.

This is the major controversy in the 1975 crisis.

In 1975, G-G, Sir John Kerr, unilaterally used S. 57 to dissolve the Australian Parliament. He unilaterally dissolved the Parliament. Up until then, and to this day since, the convention is that it’s the PM who has the prerogative to request that S. 57 be used.

Researchers consult the second reading speeches if they wish to find out what the government was thinking about.

[In answer to a student’s q. about the ability of minor parties to respond] The official Opposition has the right of reply. The minor parties don’t have any input at the second reading stage. They get their chance at the committee stage. However, if the party whips, the leader of government business in the Senate, and the leader of Opposition business allow, someone who holds the balance of power, such as Bob Brown for the Greens, for example, may be allowed to make a speech, if they so desire.

8.4 Political background to the crisis

The second reason was that there were lots of red herrings in the debate.

It was simply about an unresolvable dispute between the two houses of parliament.

But, for many, it was more than just that. For some, there was talk about Mr Whitlam acting illegally: What about ‘the loans affair’? What about middle-eastern money lenders? What about treasurer, Jim Cairns, falling in love with his parliamentary secretary and failing to act as treasurer any longer (another red-herring)? What about the G-G allegedly taking advice from the Chief Justice of the High Court, Sir Garfield Barwick? Isn’t that a constitutional matter? No, no, no. All of these are political red herrings, swimming around the core constitutional issue which relates to the problems you have in trying to link Westminster with a federal system.

Telling the difference between shit and clay:

8.5 Controversies in Australian Westminster practice

- Party politics in the parliament. When the Australian Constitution was written, in the 1890s, we did not have today’s rigid party discipline system. So the constitutional framers wrote the constitution for a very different parliament to that of the 1970s. This is particularly relevant to the Senate. The framers intended the Senate as the states’ house, but the reality is that the Senate replicates the party politics of the lower house. Australian senators don’t sit as state representatives; they sit together in party blocks. So we have party politicisation of the Australian Parliament in both houses.

- Debate about the power of the Cabinet, especially the power of the PM. Some have argued that the rigid discipline of party politics has undermined the parliament’s role as a debater of policy. Why? Because MPs are not independent; they are party representatives and will do as told by the party. The argument is that this goes against what parliament was intended to be, which was a chamber to debate the policy being formulated by Cabinet. The extension of this argument is that Westminster parliaments are characterised by what is called the ‘Tyranny of the Executive’. This means that Cabinet is supreme, and the Supremo in the Cabinet is the PM. Rigid discipline party politics, members responding not as representatives of people but of parties, loyal to the party in government, and loyal to the party leadership, equates to a situation where parliament is simply a rubber stamp of the Government – Tyranny of the Executive – a major problem in Westminster parliaments.

- In the Australian Westminster practice we have the problem that the Constitution sets up two houses with different intentions: representing the will of the people in the House of Representatives, and the will of the states in the Senate. The reality is that the Senate replicates the party politics of the lower house.

- The Power of the PM or Premier (who’s in charge?) Who has executive power in Australia? The Westminster system says that is the PM. The Australian Constitution says it is the G-G. The reality says that it is the PM.

The first constitutional crisis is the irreconcilability of the House of Reps and the Senate.

The second crisis is that two people claim to be the head of Executive power: Officially, the G-G (from the written document), and by assumption, based on the Westminster model, the PM.

- The Australian Parliament does not have parliamentary sovereignty. There are severe constraints on what it is able to legislate upon (S. 51).

Finally, Westminster or Washminster (Federal)?

We expect in general terms that Westminster conventions will apply in Australia:

- we expect Cabinet to be the centre of Government, and the PM as the head of Government

- we have a bicameral system like Britain, but unlike Britain, our upper house is elected

- We have a written constitution which limits the power of government

- And we have the combination of federalism and Westminster

And we also have a problem with our constitution:

S61 Executive power – The executive power of the Commonwealth is vested in the Queen….

S62 Federal Executive Council – There shall be a Federal Executive Council to advise the Governor-General in the government of the Commonwealth [advise, not tell, but advise], and the members of the Council shall be chosen and summoned by the Governor-General and sworn as Executive Councillors, and shall hold office during his pleasure. [my underlining]

“You dickheads thought that the people selected the government – eh? eh? Is that what you thought? The voters think that they elect the government, don’t they? BUT that’s not what our core document says. Look, these are really powerful words. They are powerful words. They come back to haunt us in 1975. The Governor-General shall choose the ministers of the Crown, and they shall hold office during his pleasure. Nothing about elections. Nothing about prime ministers. Nothing about parliament, is there? We don’t have a democracy – we have some sort of guideautocracy”

j

The Fun Stuff:

8.6 The 1975 Constitutional Crisis – Political background

Gough Whitlam: In 1972 the Australian Labor Party is elected to government. The ALP had spent the years from 1949 to 1972 in opposition. 23 years in opposition – a very long time. Federally the Labor Party looked like they would never be elected. The coalition dominated Australian politics. So, in 1972, when Whitlam brought Labor to government, it was a very exciting time. {shows the 1972 election campaign political campaign clip – features Gough in lots of ‘masculine’ pursuits – rowing, in the army, and lots with Margaret – why was this so? Because Gough, educated man, former public servant, private school educated, university educated, in a party full of boof-headed union thugs and former train drivers and what have you – he really stood out as bit of an artistic Renaissance man. He used to quote Latin at People: nil illegitimum sum carborundum – don’t let the bastards grind you down – that sort of stuff – so the party’s secretariat ran market research; asked what people thought of Gough – what they got back was that some were worried about Gough’s sexuality. A man, not interested in football, not interested in beer, and able to cite Latin, and coming from Canberra – how could you be sure about his masculinity? So to address this problem the ad agency ensured there were lots of piccies of Gough both butch and heterosexual. There is a bitter irony in this ad. Those old enough will recognise lots of the participants as being members of the ‘arts’ community … [Classic It’s Time Campaign Advertisement – ALP 1972 – from YouTube].

So Labor came to power with quite an urgent reform program. They’d been in opposition a long time, so when they came to power, wanted to do lots. Whitlam was very much what we call today a policy womp? – he was very interested – you can read these thing in his own book called The Whitlam Government 1972-75, also known in the trade as ‘I am the Greatest by Gough Whitlam’, a 700 page extravaganza, the interesting thing about which one of the interesting things – he was interested in urban and regional planning of all things…

8.7 72 and 74 elections – Senate obstructionism

Important thing to remember about both 1972 and 1974 was that whilst Labor won the contest for the lower house, they failed to win a majority in the Senate. The 1972 election saw all of the House of Representatives elected and half of the Senate, as you’d expect. The other half of the Senate had been elected in 1969 (an election which the coalition had won). The Whitlam government started to legislate – tried to get its bills through the Senate – and it could not legislate. Every bill that went before the Senate was knocked back. In 1974, the then Liberal leader, Billy Snedden, threatened Whitlam – he said if you don’t call an early election, I will block supply, I won’t let your budget through and I’ll force an election. now at the time Mr Whitlam and the Labor Party were still relatively popular with the electorate, shown by the opinion polls, and Mr Snedden was not quite so popular; he was a bit insecure – he’d been fighting off some leadership challenges. There was growing resentment toward the Whitlam government. Things started to go wrong in Australia; there were economic problems; unemployment which had been unknown since WWII, was starting to rise, and we also started to have a serious inflation problem. This was the beginning of a period of ‘stagflation’ – high unemployment, high inflation, low growth, and yet the inflation rate was indicating that really Australia should have been booming. So we’re running into economic problems. Mr Whitlam had no interest in economics whatsoever. He was immediately caught up in a whole lot of arguments with his treasurer, who wanted Australia to change economic tack, but Mr Whitlam said no – he was in the business of making big social change.

In 1974, Mr Whitlam called Billy Snedden’s bluff, and instead of Snedden blocking Supply, Mr Whitlam went to Governor-General of the time, Sir Paul Hasluck, with four pieces of legislation that had been defeated twice over a three month period, and asked the Governor-General to dissolve both houses of parliament under Section 57. And as we know, those 4 bills were to come back in 1974 in a joint sitting, when the Whitlam Labor Party won the election. It did not, however, win control of the Senate. At the time, control of the Senate was in the hands of the Democratic Labor Party?; there were also a couple of ex Liberals who were now sitting in the Senate as Independents; ? from Tasmania, and Steele Hall from SA. So the situation in the Senate, for Whitlam, was not as bad in 74 as it had been in 72, but, again, they tried to pass legislation and they weren’t succeeding. Senate obstructionism worked, and there were serious policy problems.

8.8 Overuse of S.96 to force State compliance

One of the policy problems he had, and which was to come back to haunt him, was over the use of S. 96 of the Australian Constitution. That’s the specific purpose grant section, which says that the federal Parliament can give money to the states on terms and conditions as the Parliament thinks fit. Mr Whitlam was what we call in the trade a ‘centralist’ – he didn’t like the states; he thought that the states should be abolished; that there should be national government and enhanced local government – you can read all about that in his book – there’s a huge section on local government. Of course you can’t abolish the states. As if the people of the States are going to vote themselves out of existence! Gough went into Parliament and said – right, I’m going to do things, and I’m going to force the States to follow my policies. What he did was to use Section 96 again and again and again and again.

Now this caused him a lot of trouble. He started to have fights with premiers., and it just so happened that, of the six premiers, only two of them were Labor premiers; Don Dunstan from SA, and Eric Reece in Tasmania. Everybody else was Liberal or Country Party. There were some famous challenges in the High Court, where the federal government would send money to the States, under Section 96, and the Premiers would refuse to take it. The federal government took the States to the High Court and tried to get the Court to say to the States ‘you must take the money’, but the High Court said, no, no, no, no; there’s no compulsion, the States can refuse.

That’s a big thing. (As Paul Keating once said: “You don’t want to get between a Premier and a bucket of money”). This is relevant because this deals with the constitution in two ways:

Firstly – The federal Liberal Country Party Opposition, after 1974, when Billy Snedden is replaced, is headed now by Malcolm Fraser. Mr Fraser accused Mr Whitlam of being contrary to the spirit of the Australian federal system, and he accused Mr Whitlam of, if not acting illegally, going against the spirit of the Australian Constitution by trying to use Section 96 like he was. Meanwhile, in the States, the Premiers are going to have their revenge. Both Queensland’s (Country Party) Bjelke-Peterson, and the Liberal premier of NSW, by the name of Tom Lewis. The revenge is going to occur in the Senate. Now after the 74 election the balance of power is in the hands of two Independents: ? from Tasmania, and Steele Hall from SA. Labor then loses two senators. The first senator they lose is Lionel Murphy, the Attorney General. He is appointed by Whitlam to the High Court of Australia. This caused a furore – the Conservatives were appalled (only Conservatives were allowed to make political appointments to the High Court bench. Wait a minute. Something’s terribly wrong!)

8.9 S.15 – Replacement for casual Senate vacancy

Now, S. 15 of the Australian Constitution says, at that time, if a vacancy occurs in the Senate, the governor of the state from which the senator came, shall appoint the replacement. That’s what S. 15 used to say. The Australian convention was that a State Governor would act on advice of the State Premier, and the premier would nominate someone from the same political party as the vacating senator. That was the Australian convention.