What is art? What is its nature? What purpose does it serve? What is its value? These are but a few of the fascinating ‘big questions’ which have, for centuries, occupied the minds of many. In this essay I will consider the interpretation of art, and question the extent to which it demands a three-way conversation between artist, artwork, and viewer. I will focus specifically on the interpretation of Australian Indigenous art and I will also attempt to ascertain whether there are characteristics of interpretation which are confined to Aboriginal art, or whether they are universal.

In the infancy of colonial Australia, Aboriginal art was considered as either a contradiction in terms or simply as a ‘primitive’ curiosity. Indeed, the creation of artwork per se was not an inherent part of Aboriginal culture. After all, the concept of l’art pour l’art was a limited, and Eurocentric, philosophy. However, contrary to the ignorant expectations and assumptions of the white settlers, the Indigenous peoples did have an extraordinarily long history of sophisticated culture, a large part of which placed great importance on creative representations. Since those early days of settlement there has been a slow, but inexorable, shift in both the attitude to, and the cultural production of, what was originally so loosely termed ‘primitive art’.

A large part of this paradigm shift has been due to an inevitable, and reciprocal, learning process. On the European side there has been the dawning of a much needed understanding, sometimes arrived at through enlightened attitudes, but often driven by pragmatism and the need to satisfy the demands of international opinion. On the Indigenous side there has been an adaptation to circumstance driven by the need to survive.

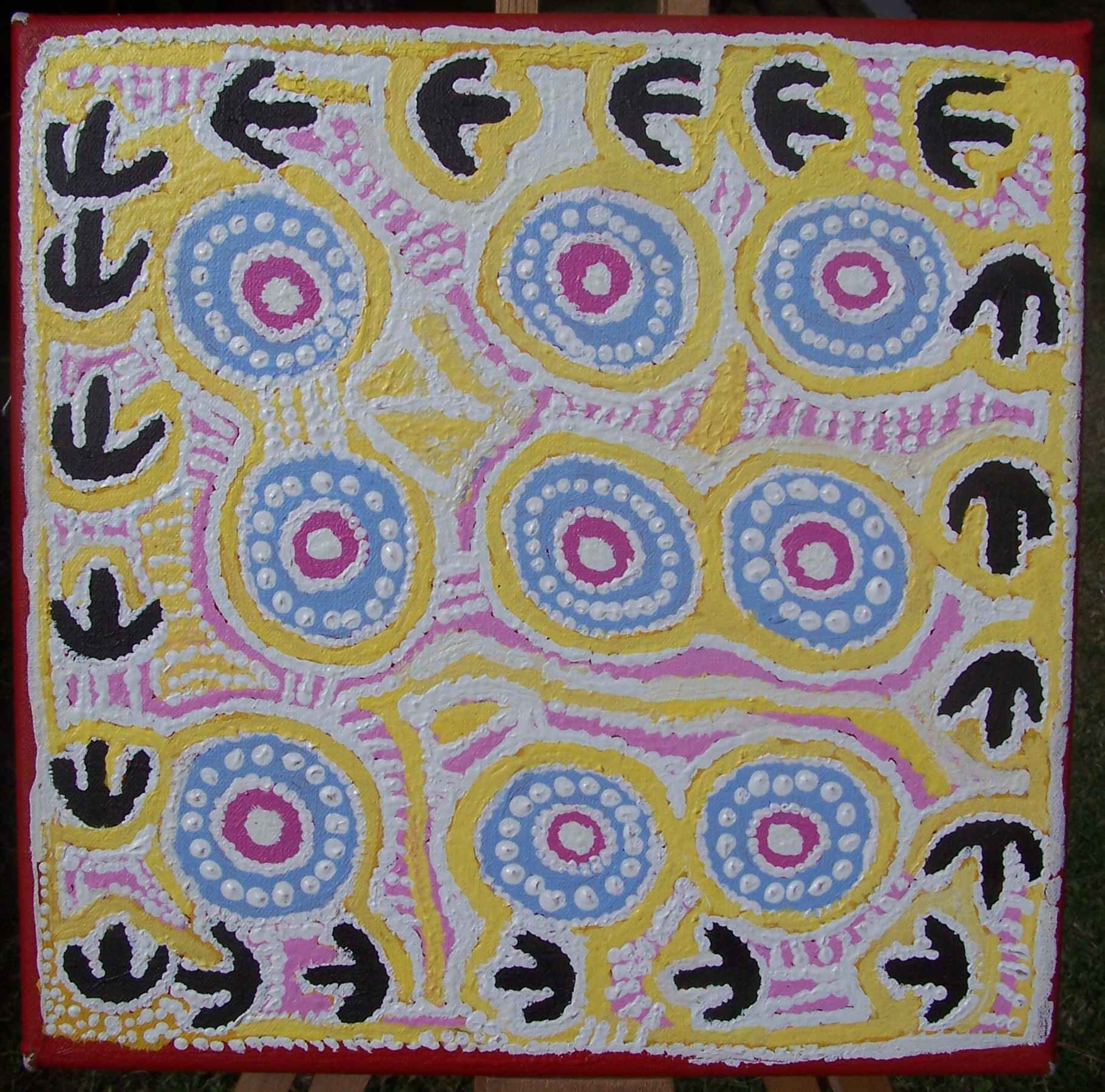

Part of the unnatural, but essential, process of adaptation undertaken by the Indigenous communities has been a transfer of styles, methods, and mediums to suit the incumbent circumstances. Driven by commercial necessity, the ‘artistic’ manifestations of traditional rituals, ceremonies, and representations, have been deliberately processed to suit the demands of an increasingly global market place. During this evolutionary process a certain amount of obfuscation has become attached to the perceived ‘meaning’ of the resulting works. Some of this obscurity has been deliberately invoked by the artists, for a variety of reasons, and some has been ‘self-imposed’ by the viewer, sometimes through simple confusion, and sometimes through a need to fulfil their own sub-consciously imposed demands of the work. In an attempt to understand this process I will examine parts of its evolution.

In some ways Charles P Mountford represents the curious dichotomy in attitude, which was often encountered within that generation of white Australians who developed and pursued an interest in Aboriginal Australians during the early to mid twentieth century, and which, to varying degrees, persists to the present day. Having left school at an early age, Mountford gained employment as a telephone mechanic with the Adelaide Post Office. Through his work he began to encounter and observe the Indigenous inhabitants of the remote parts of South Australia and the Northern Territory. His career as a part-time ethnographer began when, after finding rock carvings in the Panarimitee Hills, north of Adelaide, he combined with anthropologist Dr. Norman Tindale to write a paper on them.[1] Although his writing, and use of the vernacular, frequently indicates that his thinking was influenced by the prevailing (colonial) attitudes, his activities (such as participation in, and dismay at the results of, an inquiry into the shooting of Aboriginal people near Uluru) clearly show his respect for Aboriginal culture, and are indicative of his belief that Aboriginal life was richer and more complex than most white Australians conceded.[2] Mountford observed that despite their lack of material goods, the Aborigines enjoyed a rich philosophical and cultural life, which was founded on their concept of the world’s creation.[3]

Foremost amongst the contradictions evident within Mountford’s writing was, perhaps, his fascination with the ceremonial and religious aspects of Aboriginal culture. It is a curious, and ultimately cruel, irony that many ‘Europeans’ have been most intrigued with that in Indigenous culture to which they are least welcome. For many collectors, the most prized targets are those objects, which are held most sacred by the subjects of their fascination. Most often these valued objects will have an essential aura of mystery and secrecy, closely guarded by their owners who consider it their ancestral duty to protect those objects from violation by the uninitiated. This conflict is still in evidence with the perceived differences between the expectations of the viewer of Aboriginal art, and the expectations that the artist or artists may have of the viewer’s perceptions. When describing the practises of Pintupi (Central Desert) artists, Fred Myers reported that “The painters presume their own cultural discourses: they expect that those who see the paintings will recognize in them the assertion/demonstration of the ontological link between the painter, his/her Dreaming, the design, and the place they represented.”[4] What the painters presumed was a viewer’s recognition of their connection to the subject portrayed in their work, whether it were their connection to country, or to mythos, or both. What Aboriginal artists do not presume, however, is that a viewer would be privy to the specific details of the intricate meanings, which are often entwined beneath the surface of the images depicted. Nor do they intend, or allow, that the act of presentation of the image to the unqualified viewer carries with it the right for such a viewer to access that privileged information. On the other hand, the naïve viewer, unfamiliar with the significance of, and sensitivities associated with, the various layers of meaning of the paintings, often expects to be provided with a complete and comprehensive interpretation of the work.

In his work Aboriginal Art Wally Caruana describes art as being central to Aboriginal life. It has powerful significance as a means of connection between the present and the past and between human beings and the natural world. Furthermore, he tells us that art is a means of portraying the relationship between people and the land, while expressing both individual and group identity. In defining Aboriginal Art prior to the arrival of Europeans in the late eighteenth century, Caruana explains how it was created purely to fulfil traditional cultural needs. He contends that in varying degrees this is still true today. In this ceremonial context, ‘art’ may only be created and viewed by initiates. With the changing focus of the contemporary context however, a significant body of work has emerged which is intended for wider public consumption.[5]

This change of direction brings with it challenges in approaches to interpretation and education. Traditionally, designs derive nuances from their ceremonial, social and political context. Consequently, their interpretation is dependent on the amount of knowledge of this context possessed by both artist and viewer. Awareness is furthered by an understanding of the ‘ancestral landscape’. The level of knowledge within a community follows a specific hierarchy. For specific images, the more ritually senior man will be in possession of a range of meanings. These images may be invested with the power to transform the nature of the thing upon which they are displayed. The profane may become sacred, or the mundane, extraordinary. The application of the designs may evoke the presence of supernatural power, transforming a body from a state of dullness to one of brilliance. The senior man will choose to convey these meanings when describing ceremonial works, or may confine them to appropriate levels for alternative purposes such as youth education, or general display. It is by this means that artists are able to present their work without compromising the religious nature. Caruana describes this as being two broad levels of interpretation: the ‘inside’ level, which is restricted to those with appropriate ritual standing, and the ‘outside’, which is available to all.[6]

In Aboriginal culture, status is attained through the acquisition of knowledge rather than material possessions. Art is an expression of that knowledge. By using inherited designs, artists are asserting not only their identity, but also their rights and responsibilities. Traditionally Aboriginal societies are based on systems of kin groups and ‘moieties’. Moieties are two complementary groups, one or the other to which all people and natural phenomena belong. These moiety affiliations play an important role in determining an artist’s access to a wide range of subjects, and the way in which they may be depicted. If, through patrilineal inheritance, artists have direct rights in a particular ceremony or ‘Dreamtime’ story, they are considered the owners. They will then work in conjunction with those of the opposite moiety having secondary rights in the ceremony. These secondary rights are derived through matrilineal descent. Hence, art, as a ceremonial activity, requires cooperation between two groups having a specified relationship. This ownership of designs may be considered as equivalent to copyright.[7]

In his work, also entitled Aboriginal Art, Howard Morphy relates how this art had become known to Europeans through its place in colonial discourse. Its early European history, he said, was one of invisibility and denial.[8] If works exhibited skill of execution or satisfied concepts of aesthetics from within the European tradition, then they were likely to be attributed to an alternative source. An example of this colonial attitude is the notorious case of Sir George Grey who, in 1837, declared that the Wandjina rock paintings of the Kimberley could not be a product of Aboriginal hands. Grey’s ignorance of the country and its Indigenous inhabitants was exemplified by the poorly prepared expedition which he led into the north-west of the country, with disastrous consequences. The invisibility of Aboriginal art was consistent with the concept of terra nullius, as its existence would have made its creators similar in characteristic to the colonists, thus impinging on the portrayal of these original inhabitants as the ‘other’ – uncivilised beings who were unworthy of consideration as a valid population.[9]

This attitude of rejection of art that did not match the formalist requirements of the European conventions, still prevailed well into the twentieth century. In the 1940s and 1950s, the watercolours of Albert Namatjira received much acclaim, as much for their interpretation as being symbolic of what “civilized” Aborigines were capable of achieving, as for their skilful rendition in the style, which he had so adroitly acquired from his European teacher. Ironically, these paintings were also to achieve a good deal of controversy, being seen by some as much as a denial of Aboriginal art as recognition of it. The comparison between the European and the Indigenous concepts of art was further complicated by the fact that for much Aboriginal art, such as ceremonial sand painting, or body painting, the act of production was at least as important as the finished product, which was often ephemeral by nature.

For the traditional Warlpiri community of Yuendumu, in the Western Desert, the closest equivalent to European paintings is their sandpaintings. These sandpaintings are large and should be completed within a day to conform to the ceremonial schedule of ritual gathering. They are both situational and ephemeral. They are not self-contained texts but, rather, more akin to ‘performance pieces’ where an observer is encouraged to recognise their meaningfulness, but not their meaning. The meaning for these Warlpiri designs does not exist in the imagination of an individual artist, but in a dynamic collective, and religious discourse, which is not immediately available for transfer to the onlooker. To see these designs, learn about their meanings, and ultimately to be allowed to participate in their creation and display, demands a reciprocal conversation. The designs are learned and used within a variety of social and ceremonial settings. This is a process, which is exterior to any given painting and, therefore, is a process for which sophisticated critical knowledge of art forms is no substitute.[10]

In the European tradition, an artwork usually has well defined attributes of form, fit and function. It will usually take the form of a painting or sculpture, it will fit within the confines of a picture frame, or mount on a pedestal, within a gallery or public viewing space, and it is generally designed to provide the viewer with some sort of aesthetic or intellectual stimulation. However, the production of Aboriginal images is far removed from this static Western perception of art. From the Warlpiri observations, we see that the Aboriginal tradition of art is not confined to specific forms, does not fit into predefined spaces, and functions as a dynamic cultural, social, and ritual ingredient in the daily life of the community. The stark incongruity in these concepts has necessitated innovations in the adaptation of Aboriginal artworks to allow them to operate in the prevailing modern day exhibition space.

In this evolution, new materials and techniques have been embraced by the artists. In the same way that ‘country’ and ‘Dreaming’ are connected by common systems, such as kinship and moiety, while substance and detail vary between isolated communities, so these new forms of artistic endeavour differ in style and substance, as befits the applications of their associated community.

In Central Australia, the creation of objects for the market place, instead of the ritual and social purposes of the community, took on the new form of acrylic paints on canvas. As they moved out into the broader cultural arena of the galleries where they were displayed and offered for sale, the meaning of these objects moved out of the control of the artists. Nevertheless the Central Desert artists claim these new forms to be both “traditional” and “authentic” and that they are mularrpa – true stories, or turlku, from the tjukurrpa – the mythological past of the dreaming. Because of this, the Pintupi, from Central Australia, continue to think of their commercial work as being derived from ceremony and rock paintings, and as having value other than the pecuniary value established in the saleroom. [11]

In western Arnhem Land the rectangular form of bark painting available today is the product of an eighty-five year history of cultural contact and is derived from the interconnected motivations of Aborigines and of non-Aboriginal collectors seeking an appropriate medium of cross-cultural communication.[12] This area is the home of major rock paintings found throughout the rocky plateau, a source of attraction for researchers and collectors who found that the artists of the region also painted the interiors of their bark shelters. The Kunwinjku artists of Arnhem Land embraced these developments and see their art as a means of communicating their view of the creation of the world with a new world audience.

An interesting aspect highlighting the potential for the loss of significant cultural practises, when adapting rich and multi-faceted traditions to the limited form viable in commercial markets, is what Geoff Bardon called ‘the Haptic quality in the Aboriginal culture of Central Australia’.[13] He described the Aboriginal temperament as having a predilection to the sensitivity of touch, known as haptic sensation. This tactile quality differs entirely from the visual sensation in eyesight and was not only employed prolifically in the creation and reading of art work, but in much of the way of life. Sand mosaics, body decorations, and tjurunga patterning were created by finger painting with ochre colours or by chipping into a stone or wooden object. Rather than by visual perception, these objects would also be read almost entirely by touch. The artist understands and reveals his work through touch and not necessarily by looking at it.

Ever since the arrival of the white man, Aboriginal people have had a sad history of subjugation and exploitation. As recently as this month the Melbourne Age carried a story telling of 83 year old Aboriginal elder Banjo Morton who led a walk-off of his Alyawarr people from Ampilatwatja settlement in protest at their treatment under the 2007 ‘federal indigenous intervention’. The report describes the Alyawarr people as saying they have been treated as outcasts and isolated from white man’s decision making. Sixty-eight years previously, Banjo Morton had forced the owners of a cattle station in the NT to pay Aboriginal stockmen £1 a month when he led a walk-off in 1942. “We were getting paid only in rations, clothes and boots and we had a good win although we still grumbled it wasn’t enough,” he says.[14]

Although the current production of Aboriginal art offers many opportunities for Indigenous communities, there remains the ever present danger of exploitation and appropriation. Since demand increased in the early 1980s, a network of artists representatives, cooperatives, agents and dealers has developed. Many communities followed the lead of Papunya painters who formed an artists’ cooperative in 1972. Twenty years later, some twenty to thirty cooperatives had been established throughout the Central and Western deserts, Arnhem Land and the Kimberley.[15] In an interview with the assistant manager of the Aboriginal Galleries of Australia, a leading gallery in Spring Street, Melbourne, I was told that the majority of art work on display was the product of the gallery’s regular stable of artists. These artists worked with materials supplied by the gallery, producing the work on demand, in the gallery’s own studio near Alice Springs. Many of these works are for sale with price tags in the tens of thousands of dollars. I was unable to establish the manner or amount of remuneration received by the artists, but was left with the uncomfortable suspicion that it may be entirely disproportionate to that price commanded by the gallery.

In Bad Aboriginal Art, Eric Michaels raised the question as to whether, despite the vast cultural and semiotic distances separating us from the Warlpiri, some sense of the truth of Warlpiri philosophy may be communicated, through their paintings, to the uninitiated viewer. He questions whether they might convey some authentic vision beyond the cultural specificity of the iconic and semiotic codes employed in their construction. Are they considered as ‘art’ simply because of their agreement with current fashions of form and technique, elevated in value due to their ethnographic curiosity?[16] I think these are important questions, deserving of consideration across a broad range of Aboriginal art.

I believe that the philosophy which underpins the interpretation of art is one which is not bound by parochial borders. As with Aboriginal art, many great works of Western art are founded in ancient stories steeped in religion. And as with Aboriginal art there are many abstract expressions of Western art which may appeal to the unknowing or uninitiated viewer from a purely visceral or sensuous viewpoint. A Botticelli masterpiece, such as the Birth of Venus, or Primavera, can appeal to the viewer on a number of levels, consummate with their level of knowledge, recognition, and understanding of the rich symbology within. The more educated viewer, conversant with the figures and stories of classical mythology, stands to gain the most from the viewing experience. However the viewer unfamiliar with the underlying meaning may still marvel at the inherent beauty, and feeling, of the work.

In both European and Indigenous spheres, all contributors stand to benefit from a positive and comprehensive dialogue between the artist or artists and the viewers of their work. For the viewer, the opportunity for greater understanding offers a richer experience. It allows access to a fertile source of fascinating and illuminating history and mythos. It can demystify, and so enhance appreciation of, the inherent beauty of a work of art or theatre. For the artist it provides an appropriate response, both practical and social, for their labours. It helps them to fulfil their role as story teller. It opens communication with a wider range of interested participants. In the Australian Indigenous context, it also offers the potential for narrowing the cultural divide and assisting on the path to reconciliation between groups too long divided.

Bibliography

Bardon, Geoff. Aboriginal art of the western desert. Adelaide: Rigby, 1979.

Caruana, Wally. Aboriginal art. London: Thames and Hudson, 1993.

Charles P Mountford, photographer and ethnographer. http://samemory.sa.gov.au/site/page.cfm?u=949 (accessed February 8, 2010).

McCulloch, Susan. Contemporary aboriginal art: a guide to the rebirth of an ancient culture. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 2001.

Michaels, Eric. Bad Aboriginal art: tradition, media and technological horizons. St. Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1994.

Morphy, Howard. Aboriginal art. London: Phaidon Press, 1998.

Morphy, Howard and Margo Smith Boles. Art from the Land – dialogues with the Kluge Ruhe Collection of Australian Aboriginal Art. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1999.

Mountford, Charles P. “The Aboriginal Art of Australia.” In Oceania and Australia, Eds. Mountford, Buhler, & Barrow. London: Methuen, 1962.

Murdoch, Lindsay. “‘Outcast’ Aborigines stage red desert walk-out.” The Age, Feb 13, 2010: 1.

Myers, Fred. “Representing Culture: The Production of Discourse(s) for Aboriginal Acrylic paintings.” Cultural Anthropology Vol 6, no. 1 (1991): 34.

Taylor, Luke. “Flesh, bone, and spirit: Western Arnhem Land bark painting.” In Art from the Land – dialogues with the Kluge Ruhe Collection of Australian Aboriginal Art, edited by Howard Morphy and Margo Smith Boles. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1999.

[1] Charles P Mountford, photographer and ethnographer http://samemory.sa.gov.au/site/page.cfm?u=949

Accessed 8 February 2010

[2] Charles P Mountford, photographer and ethnographer http://samemory.sa.gov.au/site/page.cfm?u=949

Accessed 8 February 2010

[3] Charles P Mountford, The Aboriginal Art of Australia, in Oceania and Australia, Buhler, Barrow and

Mountford, Methuen: London 1962 p208

[4] Fred Myers, ‘Representing Culture: The Production of Discourse(s) for Aboriginal Acrylic paintings’ Cultural Anthropology, Vol.6, No. 1 (1991). p34.

Fred Myers is Professor and Chair of Anthropology at New York University. He is the author of a monograph on western desert people, Pintupi Country, Pintupi Self (University of California Press, 1986) and co-editor (with George Marcus) of The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Anthropology and Art (University of California Press, 1995). He is currently completing a book on the production and intercultural circulation of western desert acrylic painting. [Notes on contributors – Art From the Land p261]

[5] Wally Caruana, ‘Introduction’ from Aboriginal Art (1993). pp 7, 10

As well as being the author of author of Aboriginal Art, Wally Caruana is Senior Curator at the National Gallery of Australia where, since 1984, he has been chiefly responsible for developing the collections of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art. He has curated several major exhibitions at the Gallery including The Painters of the Wagilag Sisters Story 1937-97. He co-edited the catalogue for that exhibition with Nigel Lendon, edited Windows on the Dreaming (National Gallery of Australia & Ellsyd Press, 1989). [Notes on contributors – Art From the Land p261]

[6] Ibid pp 10, 11, 14

[7] Ibid pp 14, 15

[8] Howard Morphy. Aboriginal art. London: Phaidon Press,1998. p19

Howard Morphy is a Senior ARC Research Fellow at the Australian National University and Professor of Anthropology at University College London. As well as Aboriginal art, he has written and edited a number of books including Ancestral Connections: Art and an Aboriginal System of Knowledge (University of Chicago Press, 1991). [Notes on contributors – Art From the Land p261]

[9] Ibid pp19, 21

[10] Eric Michaels, Bad Aboriginal art: tradition, media and technological horizons. St. Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1994. pp50.1, 51.2, 52.3

[11] Fred Myers, ‘Representing Culture: The Production of Discourse(s) for Aboriginal Acrylic paintings’ Cultural Anthropology, Vol.6, No. 1 (1991) p27

[12] Luke Taylor, ‘Flesh, bone, and spirit: Western Arnhem Land bark painting’, Art from the Land – dialogues with the Kluge-Ruhe Collection of Australian Aboriginal art, Eds. Howard Morphy and Margo Smith Boles, Charlottesville: University of Virginia,1999 p27

[13] Geoff Bardon, Aboriginal art of the western desert. Adelaide: Rigby,1979. p22

[14] Lindsay Murdoch, ‘Outcast’ Aborigines stage red desert walk-out, The Age,13 Feb 2010, p1

[15] Susan McCulloch, Contemporary aboriginal art :a guide to the rebirth of an ancient culture. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 2001

[16] Eric Michaels, Bad Aboriginal art: tradition, media and technological horizons. St. Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1994. pp59, 60.1